Aug 20

Privacy is a solution

Addressing common misconceptions on an imminent Supreme Court judgement that promises to be historic

Privacy has had many adversaries who doubt its meaning, applicability and utility. A powerful opinion piece by Raju Rajagopal last week marshals concern when it seeks to caution the Supreme Court against granting a right to privacy.

The problem with the right to privacy

The recently concluded Supreme Court hearings on Aadhaar and privacy pitted a quintessentially American idea of the…www.livemint.com

Privacy is a fundamental right which was applied by the Supreme Court for decades till a cloud on its existence was raised in 2015 in the midst of arguments in the Aadhaar case. After the conclusion of hearing last month, we can shortly expect a historic judgement on the scope and ambit of the right. Till we wait a spirited public debate has provided an opportunity to engage with some common misconceptions on privacy.

Problems with Aadhaar ? Easy as one, two, three.

The first and repeated allusion is of privacy being foreign to India. This subsequently is built to premise arguments of cultural relativity to pose that we as a country do not care about privacy — compared to western countries. Or worse, the poor have no conception of it. This widespread opinion is shared by many except those which have studied the subject. One notices a range of judicial decisions in the late at the turn of the 19th century itself when Indians make privacy claims.

For instance, in the case of Gokal Prasad v. Radho in 1888, a plaintiff complains that the doors of a neighbour’s house open up to a verandah and thereby intrude into his home’s privacy. This is not an isolated instance, and frequent claims for spatial privacy over the years are made in courts. This is backed up by research in recent years that suggests that Indian’s do care about privacy. Indications are found in several empirical and interview based studies such as those conducted by P. Kumaraguru at IIIT, Delhi.

It is not without reason that activists who have dedicated their entire lives to the service of the poor and marginal communities including sanitation workers and women rescued from trafficking are petitioners before the Supreme Court.

The second point of concern is born out of care for the administrative efficiency of the government which is later narrowed down to safeguarding the Aadhaar program. The proposition that a right to privacy will undermine administrative efficiency is little more than fear mongering. Developed countries, who are utilising cutting edge technology and advances in big data have realised that without adequate privacy protections they will be putting their citizens to incredible handicaps. Even otherwise there is little reason to doubt the capacity of Indian courts to judge conflicting considerations on the basis of reference to constitutional doctrine.

Our High Courts and the Supreme Court have often faced issues of balancing the right to privacy with other competing interests in the past. They have done it for more than 45 years, till the Government and the UIDAI disputed the fundamental right to privacy. Many of the cases concerned state and social interests such as midnight domiciliary visits by the police, sexual autonomy and gender rights such as the choice of single mothers not to disclose the name of the father, medical conditions that would invite social ostracism, indiscriminate telephone tapping of political leaders, narco-analysis of suspected offenders that force in-effect confessions etc. Many of these cases, the determination was not an absolute bar on state power, but moderating it with safeguards. Such restraints serve the larger public interest.

The third but not the final critique is the likely impact of privacy on open government, more specifically the Right to Information Act. This is a curious position to take given the right to information act itself has a chapter to safeguard privacy, in which the right of an individual is balanced against the public interest served by disclosure. This is determined on a case to case basis by information commissioners.

It is also relevant to consider that through cases such as Namit Sharma v. Union of India, the interplay between the fundamental right to privacy and the statutory protections under the Right to Information Act have been deliberated by the Supreme Court.

It must also be understood that privacy, rather counterintuitively by itself creates a legal obligation of informational accountability that is the purpose of open government. Due to such a right a citizen has the ability to demand from government how their data is collected, used and disclosed. However at present due to Aadhaar an opaque system has been built which is resulting in denial in entitlements and even making access to information harder for citizens.

A “one-time exception” for Aadhaar ?

Voices against privacy are more accurately voices for Aadhaar. Even though the Supreme Court is at present not deciding its legality, there is a fear that without a, “one time exception”, Aadhaar may be ruled as unconstitutional. These apprehensions are entirely justified. There is no reason for the Supreme Court to be bound by the immediate concerns of statecraft to moderate a constitutional right that will form the very basis of individual liberty for decades and future generations. While Aadhaar’s stated aims are to achieve constitutional objectives of better serving the poor it has to be through constitutional means.

Even otherwise Aadhaar is far from a social and economic panacea. Continued data breaches, rights deprivations, mass exclusion from entitlements such as rations, high arbitrariness in deactivation etc. require an urgent public consultation on the Aadhaar program. It is pertinent to mention that this Aadhaar Act that was incorrectly certified as a money bill was passed circumventing any public scrutiny or parliamentary checks.

In addition to such a consultation, a multi-stakeholder approach needs to be undertaken by the Committee of Experts formed under the Chairmanship of Justice Srikrishna. Justice Srikrishna is well known and regarded for a report on the 1992–3 Bombay Riots. This is why the composition of the committee being dominated by government and those who have expressed public positions against privacy comes as a disappointment.

The drafting India’s privacy law without any diversity within the committee is sure to tilt the proceedings despite the best intent of the chair. To be clear there is not one civil society organisation or academic present to achieve balance. The composition of the committee does a disservice to the stature of Justice Srikrishna.

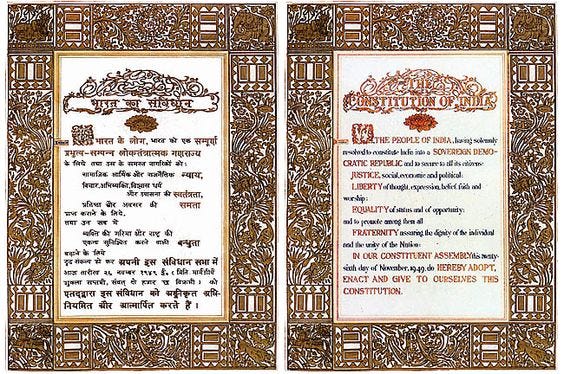

Stepping back, but looking ahead at the Supreme Court we can draw some lessons from the final address of Dr. B.R. Ambekar to the Constituent Assembly when he stated that, “[w]ithout equality, liberty would produce the supremacy of the few over the many. Equality without liberty would kill individual initiative.” Imagine economic prosperity and even security without the ability to enjoy it. That is a world that gives up on civil rights. A right to privacy will guard liberty and help in securing equality through a path that does not cause fear and coercion. To caution against such a judgement due it’s likely impact would be privileging Aadhaar over the Constitution of India.