Research from the Centre for Communication Governance suggests robust democracies are less likely to have biometric identity systems.

Published Sep 29, 2017 · 09:00 am

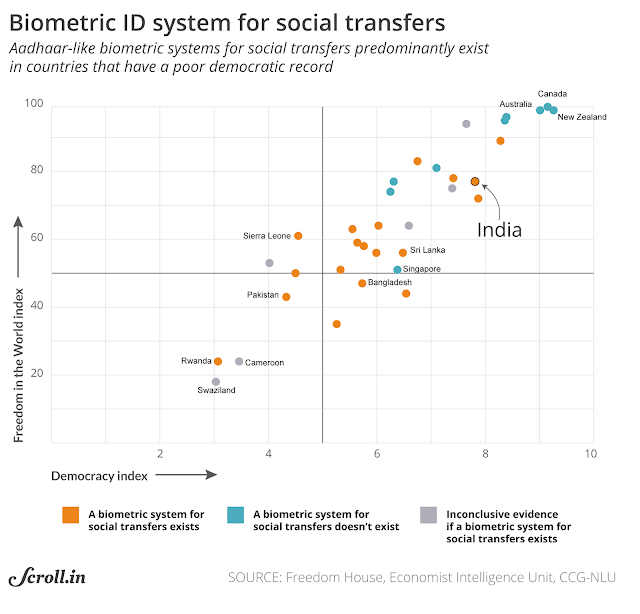

Can a country’s democratic record indicate whether it is likely to mandate a national biometric identity? Research by scholars at the National Law University, Delhi suggests there may be some correlation, at least to indicate that robust democracies have been more cautious about adopting biometric identity systems.

The Supreme Court’s decision last month upholding a fundamental Right to Privacy for all Indians has put a renewed focus on Aadhaar, India’s 12-digit biometric identity programme that has been criticised for not only violating privacy but also lacking sufficient data protection safeguards. Challenges to the Aadhaar project, in fact, prompted the Supreme Court to take up the question of a Right to Privacy, and the apex court will hear petitions against the unique identity initiative later this year.

Ahead of those hearings, researchers from the Centre for Communication Governance at the National Law University, Delhi sought to look at the adoption of biometric identity systems by countries across the world. While examining whether countries were instituting these Aadhaar-like systems, researchers from the Centre noticed a trend wherein nations with strong biometric identity systems were less likely to have robust democratic governments.

“As we gathered and analysed the data, we noticed an interesting trend where many countries that had strong biometric ID systems, also did not have strong democratic governments,” the researchers said.

So they sought to map out their research, based on data collected primarily from countries within the Commonwealth, measured against their positions on Freedom House’s Freedom in the World index and the Economist Intelligence Unit’s Democracy index. The results show a cluster of nations with less freedoms also instituting a biometric system, while others higher up the democracy index do not have similar identity programmes.

Chart: Anand Katakam

“Our findings do suggest that the stronger Commonwealth democracies tend to have public consultations, challenges before the courts, and public discussions about the various issues that a system like this poses,” the researchers said. “Most of the stronger democracies in our study also have privacy and data protection laws... It may, however, be fair to say that democracies are typically cautious in terms of whether and how they adopt biometric identity systems.”

Looking at just the Freedom Index, India sits right in the middle relative to the countries being examined here and, as the graph below shows, the lower down the index you go, the more likely the country has a biometric system for social transfers.

Edited excerpts of an email interview with Chinmayi Arun and Smitha Krishna Prasad follow:

What prompted you to undertake this research?

Centre for Communication Governance: We noticed that one of the arguments being made in defence of Aadhaar was that there are similar systems in most countries across the world. We were aware, of course, that the United Kingdom’s National Identity Cards Act, which called for biometric-based national identity cards for all citizens and an associated national identity register, was repealed after concerns were raised that the project was unnecessary, wasteful, and invaded the privacy of the registered citizens. All information collected during the initial years of the project was destroyed.

We did, however, want to engage with the argument about the prevalence of biometric identity systems being used in other countries in a fact-based, research-oriented manner. We, therefore, decided to study other countries’ biometric-based identity cards/schemes. The decision to focus on Commonwealth countries was mainly because we felt their legal systems would be more easily comparable to India.

We started our research by simply looking for the existence of biometric identity systems, and the legal frameworks for these systems with an open mind. As we gathered and analysed the data, we noticed an interesting trend where many countries that had strong biometric ID systems also did not have strong democratic governments. We then decided to map our research on biometric ID systems across Commonwealth countries, against existing research that maps the nature of government (democratic or not), in each of these countries. The Freedom in the World Index – 2017, published by Freedom House, seemed like a reasonable index to work with especially since it covered all the countries we had examined in our our research.

What were you expecting to find over the course of the research?

Centre for Communication Governance: We were curious about why other countries were adopting these systems, what models they were using and if they had found ways to address the civil liberties concerns. We went in with an open mind, to see if there were details that would be useful as we debated these questions in India. One should not be adopting or rejecting a system purely based on other countries’ choices – the underlying reasons and context are very important if we actually want to understand the choices.

What do you make of the results? Do you think there is a strong enough trend in the correlation to make some conclusions?

Centre for Communication Governance: Our findings do suggest that the stronger Commonwealth democracies tend to have public consultations, challenges before the courts, and public discussions about the various issues that a system like this poses. We have inherited our top-down processes from the United Kingdom, but the United Kingdom has a healthy tradition of public consultation and has had the courage to roll back a project that was not working. There are also ongoing discussions and protests against the smart ID system in South Africa.

Most of the stronger democracies in our study also have privacy and data protection laws. We are still in the process of analysing and understanding the specific safeguards contained in these laws. It may, however, be fair to say that democracies are typically cautious in terms of whether and how they adopt biometric identity systems.

From carrying out this research, what is your sense of the way governments are using biometric IDs? Is there a clear trend, regardless of position on the political freedom spectrum, of more countries using biometrics for specific things – say as a national ID or for voting?

Centre for Communication Governance: We have seen that a number of countries seem to be moving towards implementing national ID systems. However, not all of these are necessarily biometric-based. Where biometric systems are being implemented, they seem to be in place to help with passport / visa applications, law enforcement, or KYC (know your customer) for financial transactions.

As a follow-up to that, do you believe that countries that are using biometrics for social welfare delivery are likely to also be using that ID for other things like voting and so on?

Centre for Communication Governance: A few of the countries we have seen on the list seem to be using biometric or non-biometric national IDs for delivery of social welfare benefits. A few are using the ID systems across different types of services. However, it is hard to tell what direction they will move in, although we have noticed that many organisations writing about these systems are critical or questioning of these systems, especially from the point of view of function-creep (or the widening of the use of a system beyond its original purpose). Questions are already being asked in South Africa about their ID system being accessed by law enforcement, and being used to profile and discriminate against marginalised people.

What takeaways do you have from the legislation aspect mentioned? Would we need more research to judge the relative strength of data privacy laws if they exist?

Centre for Communication Governance: Some countries, especially the ones higher up the democracy index, do seem to have privacy laws in place. We will, however, need to study these laws more, and possibly get inputs from legal experts in these countries to understand the specific safeguards that they offer to mitigate potential harm arising from the ID systems.

Is there any sense, when looking qualitatively at the aspects of biometric systems, that countries are using ‘best practices’ based on one nation’s model like, say Aadhaar?

Centre for Communication Governance: It is possible that this is the case. However, we will need to undertake further research to see if there is a specific pattern. We have also noticed other interesting links between the systems adopted by different countries: for example, service providers getting contracts for the supporting infrastructure for these systems in some other countries have also got contracts for the Aadhaar project. It would be worth examining this trend more closely.

Where does the research go from here? What would you want people to take away from this information, and what sort of follow-ups are you expecting, either that you will be working on, or what others may be able to do based on your data?

Centre for Communication Governance: We hope our work so far is useful and triggers more data-oriented, detailed investigation by others. We plan to continue our research by adding more countries to this list.

We would also like to analyse the particulars of the data protection and privacy frameworks that operate in the countries we are studying. The Centre for Communication Governance is an academic research centre at the National Law University, Delhi. Our aim is to use research to facilitate informed public debate, and effective, research-led policy making in relation to issues at the intersection of technology and law.