Anjuli Bhargava

Mary’s predicament is about to be resolved though she doesn’t know it yet. She will soon get an identity and a basic bank account, and above all, a means to prove to dozens of official agencies that she is a citizen. Provided, of course, that a former technology entrepreneur who is currently leading the government’s identification project gets his act right.

Meanwhile, in his office in North Block in New Delhi, chief economic advisor (CEA) Kaushik Basu is pondering over how to stop the enormous leakages in the government’s various subsidy schemes. Though the government will spend close to Rs 1 lakh crore as subsidy for the poor this year through its welfare schemes, an estimated 60 per cent of this will never reach the intended beneficiaries. From food sent to ration shops meant for the very poor to money meant for the Mahatma Gandhi National Rural Employment Guarantee Act (MNREGA), everything gets pilfered and only a fraction ever reaches the intended beneficiaries. This has continued for decades. But now, Basu has the solution in sight — provided the same technology entrepreneur and his team can prove that direct transfer of funds to intended beneficiaries can be successfully carried out.

In his own office, just a stone’s throw away from Basu’s office, Nandan Nilekani, co-founder of Infosys and currently chairman of the Unique Identification Authority of India (UIDAI), is satisfied with the way his job has changed. What had begun as the UID project — a foolproof method of providing an identification number to each and every Indian citizen — has now metamorphosed into a massive transformational project that can change the face of India.

As the next stage of India’s largest public sector project since Independence begins, Aadhaar envisages opening basic bank accounts, allowing money transfer from one area to the other, using mobile technology in conjunction with the Aadhaar number for transactions and even direct transfer of subsidies to the very poor using their unique identity numbers. Nilekani’s motley team of bureaucrats, bankers and technologists are out to sort out all manner of problems that have plagued India’s poor.

Will their audacious dream work? There are still plenty of question marks about the project, including the fact that so far it has reached only very few people. And there are many issues, big and small, that need to be sorted out, details that need ironing out, and kinks that need straightening before one can pronounce that the whole affair is working smoothly. But what is apparent is that the team has moved from a mere identification project to something much, much bigger — and it is this second phase that will make all the difference.

Key To Many Doors

Nilekani says that if the Aadhaar project meets its goals, it will be because of the team, all of whom are fired with evangelist fervour. Ram Sevak Sharma, former principal secretary for information technology in Jharkhand and currently director-general of the Aadhaar project, is certainly a man with a mission. Then, there is Ashok Pal Singh, deputy director-general of UIDAI, who is on deputation from the Indian postal service and is now one of the most dedicated members of the Aadhaar project, leading the financial inclusion initiative. Rajesh Bansal has been lent to the project by India’s central bank to work out the financial nitty gritty. Viral Shah, PhD in computer sciences, has no government background — he simply met Nilekani at a conference in the US and talked himself into the project. He worked a whole year without pay before Nilekani put him on the rolls. Shah has the onerous task of making the technology back-end of the complex financial inclusion model work.

“We have been travelling and trying to bring all banks and financial institutions on board,” says Sharma. Not an easy task given that many banks do not find it financially remunerative to provide banking facilities to the very poor in remote areas. Having branches or even ATMs that can be serviced in far flung areas is costly — and often, the total money deposited by clients in these areas is too little to justify the expense. Also, transaction values are low and so a bank’s revenues from the accounts can be very low.

Still, the team is gung ho about the whole affair. It has powerful backing — including CEA Basu and deputy chairman of the Planning Commission, Montek Singh Ahluwalia. It has also managed to get the blessings of the Reserve Bank of India, which has agreed to the Aadhaar identity being the KYC norm for all banks operating in India. The project team has already talked to over 50 banks and it expects to have all of them, as well as the others, on board by the end of the year, by when about 60 banks will be empanelled to open Aadhaar-linked accounts.

At present, only 250 million Indians have bank accounts, according to some estimates. If the Aadhaar-linked accounts take off, the number will go up three times, says the project team. “You can imagine what an opportunity it is for the banking and insurance sector,” adds Bansal.

Already, in the first 5 million enrolments that have been carried out by UIDAI, 88 per cent UID holders have chosen to open a new bank account. “If I go by this trend, we would expect some 800 million new bank accounts to be opened. Even if I assume that this will come down since many people may choose to link to existing accounts and not open a new account, at least 500 million new bank accounts will be opened,” says Singh.

What about the capital costs involved in setting up branches or ATMs in far-flung areas with very poor customers and small populations? The team has a way out for this as well, with the help of the central bank.

With Aadhaar, for every 2,000 accounts that a bank acquires, it is required to put up one business correspondent in that district so that these accounts can be serviced (the aim is to have two business correspondents in every district so that some competition creeps in). The business correspondent will use micro ATMs to provide services and service accounts.

The big hurdle for the micro ATM concept was verification of identities of customers. Aadhaar solves that problem. All that a business correspondent needs is a small machine that will match the customer’s thumb print with the central database. It is an elegant solution.

The second step is allowing micro transfers of money from one part of India to another. Once that works out satisfactorily, an immigrant working in, say, Mumbai can send a part of his salary or savings back home to his village in, say, Kerala, without any hassle and without having to pay hefty transfer fees.

For every individual, including infants.. Enables identification, and is for every resident

Will collect demographic and biometric information to establish uniqueness of individual

Voluntary

For every resident, irrespective of existing documentation

Each individual will be given a single unique ID number

UIDAI will enable a universal identity infrastructure that any ID-based application, such as ration card, passport, etc., can use

UIDAI will give a “Yes” or “No” response for any identification authentication queries

Another card

One per family

Establishes citizenship and is only for Indians

Will collect profiling information such as caste, religion, language, etc.

Mandatory

Only for individuals who possess identification documents

Individual can obtain multiple Aadhaars

Aadhaar will replace all other IDs

UIDAI information will be accessible to public and private agencies

UIDAI is looking to cover 600,000 villages through 1.2 million business correspondents. Adds Basu: “A banking system of the kind that we are envisaging, whereby the banker goes to the customer’s doorstep, identifies the customer using a hand-held device and the Aadhaar identification, and acts as a human ATM, can transform India’s financial architecture. This system can free the poor to migrate to where the opportunities are the greatest, without fearing that they cannot access their savings or get their subsidised rations. On this, India has the potential to develop a pioneering model for all emerging nations to use.” As things stand now, the poor have to pay a premium to access the same services as the rich.

A study by Boston Consulting group on financial inclusion has estimated that the penetration of formal financial services can go up from around 47 per cent to 65 per cent with an additional profit potential of Rs 1,500 crore for the financial services providers by the fifth year (subject to various assumptions and conditions). The study estimates that remittances could be made at a fee of 3 per cent of the amount or loans could be provided at 22-28 per cent, which is much lower than the informal sector (5-10 per cent for remittances and 35-100 per cent for loans). The study has further estimated how penetration can be deeper and costs can be lowered further if the policy makers (state governments) create an enabling ecosystem through regulatory and policy changes.

Re-engineering Public Services

Although Singh says Aadhaar is not the solution to the nation’s problems, it could well be used to resolve some of them. The second leg of financial inclusion is where UIDAI is working very closely with all state governments so that any benefits that are transferred through any social security or welfare scheme is done through Aadhaar-enabled bank accounts. At present, leakages are high and so is corruption. In many welfare schemes, the money or benefit that is required to be disbursed is paid out through contractors who demand a cut. In some villages in Bihar, for example, the cut can be as high as 50 per cent. “This (Aadhaar) will break the nexus. The beneficiary does not need to go on a fixed day at a fixed time to a fixed spot and meet a fixed contractor. He can go to any available business correspondent on whichever day and at whatever time,” explains Singh.

One of the main advantages of using Aadhaar would be that the benefit would reach only the beneficiary, directly, and no one else. “Due to the Aadhaar authentication process, there is no way to forge, duplicate or wrongly identify the beneficiary,” explains Bansal.

Stumbling Blocks

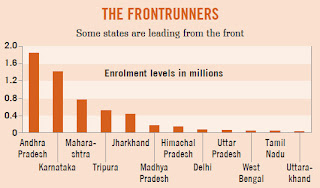

Barring the fact that state governments are slow to change, many sceptics have raised the issue that a system that will reduce discretion and, therefore, the opportunity of various stakeholders to take a cut, will meet stiff resistance. Many feel that the whole process as envisaged by the UIDAI sounds “too good to be true” or “utopian”. While some states are ahead of others — Karnataka, Tripura, Jharkhand, Andhra Pradesh lead both in terms of enrolment and their keenness to adopt Aadhaar for state-level payments — the UIDAI team says all other states are also willing to come on board. “Initially, there may have been some resistance. But now, as many states realise the potential and scope, they are coming on board. It is an idea whose time has come. All the stars, so to speak, are positioned favourably,” adds Sharma in a lighter vein.

Nilekani points out that while Aadhaar can be used very effectively to better deliver welfare funds, it is not to be confused with policy changes. For instance, whether or not the government decides to move to a cash subsidy instead of providing wheat and rice to the poor is a separate matter. The Aadhaar number can help the state identify its beneficiary clearly and help deliver the subsidy straight to the target. It is a grand dream. Basu, Nilekani, Ahluwalia, Sharma, Singh, Bansal and the others are actually re-imagining India.

So far, 88 per cent of Aadhaar card holders have opted for Aadhaarenabled bank accounts

Opening a bank account using Aadhaar will bring the cost down to almost nil from Rs 200-250 now

At present, only 10 per cent of all loans taken is through the formal banking sector

By one estimate, the cost of remitting funds domestically in the informal sector is 5-10 per cent. This can become nil through the use of micro ATMs and business correspondents

At present, close to Rs 1 lakh crore of subsidy payments flow to beneficiaries. Using Aadhaar will minimise leakages

5.5 million enrolments have been done; 4.5 million cards issued