Why this Blog ? News articles in the Wide World of Web, quite often disappear with time, when they are relocated as archives with a different url. Archives in this blog serve as a library for those who are interested in doing Research on Aadhaar Related Topics. Articles are published with details of original publication date and the url.

Aadhaar

The UIDAI has taken two successive governments in India and the entire world for a ride. It identifies nothing. It is not unique. The entire UID data has never been verified and audited. The UID cannot be used for governance, financial databases or anything. It’s use is the biggest threat to national security since independence. – Anupam Saraph 2018

When I opposed Aadhaar in 2010 , I was called a BJP stooge. In 2016 I am still opposing Aadhaar for the same reasons and I am told I am a Congress die hard. No one wants to see why I oppose Aadhaar as it is too difficult. Plus Aadhaar is FREE so why not get one ? Ram Krishnaswamy

First they ignore you, then they laugh at you, then they fight you, then you win.-Mahatma Gandhi

In matters of conscience, the law of the majority has no place.Mahatma Gandhi

“The invasion of privacy is of no consequence because privacy is not a fundamental right and has no meaning under Article 21. The right to privacy is not a guaranteed under the constitution, because privacy is not a fundamental right.” Article 21 of the Indian constitution refers to the right to life and liberty -Attorney General Mukul Rohatgi

“There is merit in the complaints. You are unwittingly allowing snooping, harassment and commercial exploitation. The information about an individual obtained by the UIDAI while issuing an Aadhaar card shall not be used for any other purpose, save as above, except as may be directed by a court for the purpose of criminal investigation.”-A three judge bench headed by Justice J Chelameswar said in an interim order.

Legal scholar Usha Ramanathan describes UID as an inverse of sunshine laws like the Right to Information. While the RTI makes the state transparent to the citizen, the UID does the inverse: it makes the citizen transparent to the state, she says.

Good idea gone bad

I have written earlier that UID/Aadhaar was a poorly designed, unreliable and expensive solution to the really good idea of providing national identification for over a billion Indians. My petition contends that UID in its current form violates the right to privacy of a citizen, guaranteed under Article 21 of the Constitution. This is because sensitive biometric and demographic information of citizens are with enrolment agencies, registrars and sub-registrars who have no legal liability for any misuse of this data. This petition has opened up the larger discussion on privacy rights for Indians. The current Article 21 interpretation by the Supreme Court was done decades ago, before the advent of internet and today’s technology and all the new privacy challenges that have arisen as a consequence.

Rajeev Chandrasekhar, MP Rajya Sabha

“What is Aadhaar? There is enormous confusion. That Aadhaar will identify people who are entitled for subsidy. No. Aadhaar doesn’t determine who is eligible and who isn’t,” Jairam Ramesh

But Aadhaar has been mythologised during the previous government by its creators into some technology super force that will transform governance in a miraculous manner. I even read an article recently that compared Aadhaar to some revolution and quoted a 1930s historian, Will Durant.Rajeev Chandrasekhar, Rajya Sabha MP

“I know you will say that it is not mandatory. But, it is compulsorily mandatorily voluntary,” Jairam Ramesh, Rajya Saba April 2017.

August 24, 2017: The nine-judge Constitution Bench rules that right to privacy is “intrinsic to life and liberty”and is inherently protected under the various fundamental freedoms enshrined under Part III of the Indian Constitution

"Never doubt that a small group of thoughtful, committed citizens can change the World; indeed it's the only thing that ever has"

“Arguing that you don’t care about the right to privacy because you have nothing to hide is no different than saying you don’t care about free speech because you have nothing to say.” -Edward Snowden

In the Supreme Court, Meenakshi Arora, one of the senior counsel in the case, compared it to living under a general, perpetual, nation-wide criminal warrant.

Had never thought of it that way, but living in the Aadhaar universe is like living in a prison. All of us are treated like criminals with barely any rights or recourse and gatekeepers have absolute power on you and your life.

Announcing the launch of the # BreakAadhaarChainscampaign, culminating with events in multiple cities on 12th Jan. This is the last opportunity to make your voice heard before the Supreme Court hearings start on 17th Jan 2018. In collaboration with @no2uidand@rozi_roti.

UIDAI's security seems to be founded on four time tested pillars of security idiocy

1) Denial

2) Issue fiats and point finger

3) Shoot messenger

4) Bury head in sand.

God Save India

Monday, October 31, 2011

1756 - Aadhar should have names of father, husband for women: Ex-CEC - IBN Live

1755 - UID project to face first major test next month - Economic Times

The identification system will be synced to the Mahatma Gandhi National Rural Employment Guarantee Scheme in five blocks of the state early next month, Nandan Nilekani, the chairman of the Unique ID Authority of India, said. The state government and banks will use this database to open bank accounts and transfer funds for thousands of beneficiaries under the Centre's flagship scheme.

The authority, asked with issuing a unique 12-digit 'Aadhaar' number to all Indian residents, is banking on the success of the pilot project to build a case for more funds and wider scale of coverage. It is also hoping to counter recent criticism of its administrative structure and expenditure.

"We have just started a pilot project linked to NREGA in Jharkhand and by next month we will launch the first online authentication system, which can give banks access to the details of beneficiaries online," Nilekani said. The 'Aadhaar' number will be the key to the holder's personal details and is meant to serve as a single source of authentication for a host of public services.

Through this, the authority hopes to check embezzlement of public funds and weed out fake identities. The result of the Jharkhand project will help authorities decide whether the system can be scaled up and used nationwide for opening bank accounts, issuing of driving licences, ration cards, passports, etc.

"This will also be used to enable payments through business correspondents in NREGA using a biometric authentication system," Nilekani added. So far, the Reserve Bank of India and the finance ministry have mandated the UIDAI number as a valid "know-your--customer" document for opening bank accounts, but are yet to allow online verification.

The authority, which has enrolled around 110 million people in its systems, is talking to various stakeholders, such as telecom department, to make 'Aadhaar' a valid document to access services. Nilekani said that three states have recognised the system's identity proof for various government services.

"We are trying to make more state governments agree to this," he added. The authority has come under fire from some government departments over its functioning and spending. In September, the Registrar General of India (RGI), which is also collecting biometric data as part of its National Population Register, said the data collected by UIDAI's registrar agencies was not reliable, as they were not following the parameters set for the NPR.

The criticism led to UIDAI's demand for Rs 15,000 crore to scale-up coverage being rejected by the Expenditure Finance Commission last month. "The Registrar General has expressed some reservations on using the data collected by non NPR registrars. That is the only contention which will be resolved by the cabinet," Nilekani said.

The decision on whether UIDAI-appointed registrars can collect data will be taken by the Cabinet Committee on UIDAI. The UIDAI was also criticised by some sections of the Planning Commission on its administrative structure while the country's official auditor, CAG, initiated a pilot performance audit on the authority on October 3.

"We have resolved all issues and are doing our job. The CAG is doing its job. We have nothing to hide. It's all transparent," Nilekani said.

1754 - Glitches in project to link LPG connections to Aadhaar

The Unique Identification Authority of India and the Ministry of Petroleum and Natural Gas selected Padma Gas Agency, Madhu Gas Service and Mahalaxmi Gas Agency to conduct the pilot and requested their customers to submit their Aadhaar numbers before October 31 this year.

But, out of the one lakh LPG connections with the three agencies, hardly three per cent of customers have submitted their Aadhaar number, while the rest have got neither their Aadhaar number nor their enrolment number despite registering months ago.

UIDAI has completed 3.6 crore enrolments in the state, but it has managed to issue only 53 lakh Aadhaar numbers, which constitutes hardly 15 per cent of the total enrolments.

The blame game continues between UIDAI, gas agents and petroleum companies. With such a lukewarm response from the public, it is impossible to go ahead with the project.

“If UIDAI gives an appointment to customers at a later date for enrolling, then we cannot conduct the pilot since it delays the whole process,” said B. Madhavi, proprietor of Madhu Gas Agency.

K. Srinivas Rao, chief regional manager (LPG), Hindustan Petroleum Corporation Ltd, said that they need at least 70 per cent response to proceed any further with the study.

1753 - Aadhaar card must for LPG refills - The Hindu

The Ministry of Petroleum and Natural Gas has brought in an amendment to its Liquefied Petroleum Gas (Regulation of Supply and Distribution) Order 2000 making the Unique Identification Number (UID) under the Aadhaar project must for availing LPG refills.

The move is aimed at removing multiple connections and those availing cylinders in third party name and to clean up the LPG consumer base, as the government was spending heavily on subsidising the domestic LPG cylinders.

With people not showing keen interest in availing the UID or Aadhaar cards, the move of the Petroleum and Natural Gas Ministry is expected to increase the enrolment for Aadhaar.

The Ministry in its circular dated October 13, 2011 has announced the amendment to the LPG Regulation of Supply and Distribution order 2011. The Ministry's decision to make Petroleum Corporations sensitise distributors on Aadhaar card for availing refills has been published in the Gazette of India vide notification dated September 26.

The order has come into effect from the date of publication of the gazette notification.

The decision to make Aadhaar UID mandatory has been done in exercise of powers conferred under Section 3 of the Essential Commodities Act of 1955 (10 of 1955).

The amended order reads as follows: No distributor of a Government Oil Company shall supply LPG cylinder to any household unless the head of such a household furnishes Aadhaar number for each member of his or her household to the distributor within three months from the date of notification of such area.

Notification of such area means an area notified for enrolment for availing Aadhaar number i.e. UID. Many major towns in Western Tamil Nadu came under Aadhaar enrolment notification in June and July of 2011.

Officials of the Oil Corporations in Western Tamil Nadu when contacted said that distributors had been asked to sensitise consumers on the need for availing the Aadhar numbers at the earliest for availing uninterrupted supply of LPG refill.

Consumers will be given reasonable time to comply with the directive.

1752 - Google: Governments seek more about you than ever - CNet

"There is simply no excuse for Microsoft, Yahoo, Twitter, and Facebook not to provide the same data," he said. "These firms monetize our data, and they don't want to give us any reason or cause for concern about entrusting them with our data, but they all need to step up and follow Google's lead."

In a blog post on the report, Dorothy Chou, senior policy analyst at Google, suggested that the ultimate goal with the report is to encourage more user-friendly policies.

Elinor Mills covers Internet security and privacy. She joined CNET News in 2005 after working as a foreign correspondent for Reuters in Portugal and writing for The Industry Standard, the IDG News Service, and the Associated Press.

1751 - EXPOSED Data on a UID Partner - Open Magazine

KOCHI ~ Accenture Services, one of the three companies awarded the Rs 2,000 crore tender for generating a biometric database for the Unique Identification Authority of India, has charges of kickbacks, delays and over budgeting against it in the US. Just last month, Accenture arrived at a $ 63.7 million settlement over kickbacks it took for giving out government contracts.

Among the three companies given the contract by the UID Authority, Accenture has the majority of the work. Of 10 fingerprints collected, Accenture will get five, Mahindra Satyam three and L-I Identity Solutions two. The project will either run up to two years or until 200 million enrolments.

Sunday, October 30, 2011

1750 - Press Note Morpho, Safran led consortium & Mahindra Satyam were given contract by UIDAI

Press Note

Morpho, Safran led consortium & Mahindra Satyam were given contract by UIDAI

UIDAI awarded by World Identification Congress sponsored by Morpho, French MNC

Election Commission, UIDAI and National Population Register (NPR) Providing ID, Which one to Choose?

New Delhi: It has come to light that Nandan Manohar Nilekani who heads Unique Identification Authority of India (UIDAI) was given ID Limelight Award at the ID WORLD International Congress in Italy. This year the 10th edition of the ID WORLD International Congress is planned in Milan, Italy during November 2-4. The key sponsors of Congress include Morpho (Safran group), a French multinational corporation specializing in ID credentials solutions incorporating biometrics application in passports, visas, ID documents, health and social benefits, elections, etc. Its subsidiary, Sagem Morpho Security Pvt. Ltd has been awarded contract for the purchase of Biometric Authentication Devices on February 2, 2011 by the UIDAI.

Earlier, on July 30, 2010, in a joint press release, it was announced that “the Mahindra Satyam and Morpho led consortium has been selected as one of the key partners to implement and deliver the Aadhaar program by UIDAI (Unique Identification Authority of India).”

This means that at least two contracts have been awarded to the French conglomerate led consortium. Is it a coincidence that Morpho (Safran group) sponsored the award to Chairman, UIDAI and the former got a contract from the latter?

Incidentally, Nilekani was given the award at the ID WORLD International Congress in 2010 held in Milan from November 16 to 18, 2010. One of the two Platinum Sponsors was Morpho (Safran group), a French high-technology company with three core businesses: Aerospace, Defense and Security.

Nilekani was given the award "For being the force behind a transformational project ID project in India...and "to provide identification cards for each resident across the country and would be used primarily as the basis for efficient delivery of welfare services. It would also act as a tool for effective monitoring of various programs and schemes of the Government." Citizens Forum for Civil Liberties (CFCL) contends that there is a conflict of interest and it appears to be an act done in lieu of the contract.

It may been noted that UIDAI awarded contracts to three companies namely, Satyam Computer Services Ltd. (Mahindra Satyam), as part of a “Morpho led consortium”, L1 Identity Solutions Operating Company and Accenture Services Pvt. Ltd of USA for the “Implementation of Biometric Solution for UIDAI” on July 30, 2010.

It merits attention that these days newspapers are flooded with advertisements of Election Commission of India, UIDAI and National Population Register (NPR) for providing ID, one does not know which one to choose. Will the donor driven NGOs who are acting as enrollers for UID/NPR enlighten the citizens? Advertisements attached.

In UID/Aadhaar Enrolment Form, Column 9 reads: "I have no objection to the UIDAI sharing information provided by me to the UIDAI with agencies engaged in delivery of welfare services". In front of this column, there is a "Yes" and "No" option. Irrespective of what option residents of India exercise (which is being ticked automatically by the enroler in any case as of now), the fact is this information being collected for creating Centralized Identity Data Register (CIDR) and National Population Register (column 7) will be handed over to biometric technology companies like Satyam Computer Services/Sagem Morpho, L1 Identities Solutions and Accenture Services of all shades who have already been awarded contracts. (The UID/Aadhaar Form is attached.

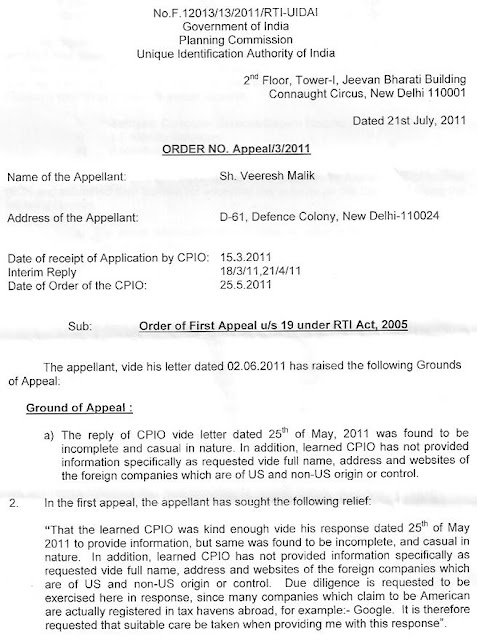

It is alarming to note that Davinder Kumar, Deputy Director General of Unique Identification Authority of India (UIDAI) will have residents/ citizens of India believe that the three transnational biometric technology companies working with foreign intelligence agencies namely:1) Mahindra Satyam Computer Services/Sagem Morpho, 2) L1 Identities Solutions and 3) Accenture Services who have been awarded contracts by UIDAI that “There are no means to verify whether the said companies are of US origin or not” in a reply to Right to Information (RTI) application dated 21st July, 2011.

CFCL takes the opportunity to inform UIDAI officials like Nilekani and Davinder Kumar the “means to verify” the country of the origin of three companies in questions.

http://www.morpho.com/qui-sommes-nous/implantations-internationales/morpho-en-inde/?lang=en

It Press Release at http://www.morpho.com/evenements-et-actualites-348/presse/mahindra-satyam-and-morpho-selected-to-deliver-india-s-next-generation-unique-identification-number-program?lang=en reveal its partnership with Mahindra Satyam. Its parent company’s website is www.safran-group.com

The second company, L1 Identities Solutions is headquartered in Stamford, Connecticut, U.S website and its press releases at http://ir.l1id.com/releases.cfm?header=news reveal that the company received $24.5 Million in Purchase Orders in the Initial Phase of India's Unique Identification Number Program for Certified Agile TP(TM) Fingerprint Slap Devices and Mobile-Eyes(TM) Iris Cameras. ( http://ir.l1id.com/releasedetail.cfm?ReleaseID=509971).

On July 19, 2011, L-1 Identity Solutions and Safran, Paris announced that in connection with the pending acquisition of L-1 by Safran, the parties have reached a final agreement on the terms of a definitive mitigation agreement with the United States government. L-1 and Safran were notified by the Committee on Foreign Investment in the United States (CFIUS) on July 19, 2011 that the investigation of the merger transaction is complete and that there are no unresolved national security concerns with respect to the transaction. With CFIUS approval for the merger, and having satisfied all other conditions required prior to closing, the parties intend to complete the merger transaction within the next five business days. Robert V. LaPenta, Chairman, President and CEO of L-1 Identity Solutions said, "The combination of L-1 and Safran Morpho with our complementary technologies, markets and promising synergies will result in the leading worldwide-wide provider of identity solutions today and into the future."

As a consequence of Safran’s purchase of L-1 Identity Solutions, the de-duplication contracts of UIDAI’s CIDR and Home Ministry’s NPR which was given to two companies on July 30, 2010, both contracts are with one company now.

It seems to be a surveillance movement based on global ID card. Commenting on the merger of the two biometric technology companies, Mark Lerner, the author of the book “Your Body is Your ID” says, “Safran is a French company, 30% owned by the French government”. Safran has a 40 year partnership with China in the aerospace and the security sectors too.

The third company, Accenture, a US company headquartered in Dublin, Republic of Ireland. It won US Department of Homeland Security’s contract for five years to design and implement the United States Visitor and Immigrant Status Indicator Technology (US-VISIT) program based on biometric technology for checking identities of foreigners visiting USA. The contract includes five base years plus five option years mandated by U.S. Congress for Smart Border Alliance project. It is one of the main privatized gatekeepers of US borders.

Now will UIDAI and Home Ministry explain whether or not they blundered in giving contracts to these above mentioned companies? Feigning ignorance about their country of origin is not a pardonable act for sure.

For Details: Gopal Krishna, Citizens Forum for Civil Liberties (CFCL)/ToxicsWatch Alliance, Mb: 9818089660, E-mail: krishna1715@gmail.com

1749 - Massive Biometric Project Gives Millions of Indians an ID - Wired

- By Vince Beiser

- August 19, 2011 | 1:27 pm |

- Wired September 2011

Photo: Jonathan Torgovnik; Fingerprints: Getty

The courtyard, just off a busy street in a Delhi slum called Mongolpuri, is buzzing with people—men in plastic sandals arguing with one another, women in saris holding babies on their hips, skinny young guys chattering on cheap cell phones. New arrivals take up positions at the end of a long queue leading to the gated entry of a low cement building. Every so often, a worker opens the gate briefly and people elbow their way inside onto a dimly lit stairway, four or five on each step. Slowly they work their way upward to a second-story landing, where they are stopped again by a steel grille.

After a long wait, a lean woman in a sequined red sari, three children in tow, has finally made it to the head of the line. Her name is Kiran; like many poor Indians, she uses just one name. She and her school-age brood stare curiously through the grille at the people and machines on the other side. Eventually, an unsmiling man in a collared shirt lets them into the big open room. People crowd around mismatched tables scattered with computers, printers, and scanners. Bedsheets nailed up over the windows filter the sun but not the racket of diesel buses and clattering bicycles outside. Kiran glances at the brightly colored posters in Hindi and English on the walls. They don’t tell her much, though, since she can’t read.

A neatly dressed middle-aged man leads the children to a nearby table, and a brisk young woman in a green skirt sits Kiran down at another. The young woman takes her own seat in front of a Samsung laptop, picks up a slim gray plastic box from the cluttered tabletop, and shows Kiran how to look into the opening at one end. Kiran puts it up to her face and for a moment sees nothing but blackness. Then suddenly two bright circles of light flare out. Kiran’s eyes, blinking and uncertain, appear on the laptop screen, magnified tenfold. Click. The oversize eyes freeze on the screen. Kiran’s irises have just been captured.

Kiran has never touched or even seen a real computer, let alone an iris scanner. She thinks she’s 32, but she’s not sure exactly when she was born. Kiran has no birth certificate, or ID of any kind for that matter—no driver’s license, no voting card, nothing at all to document her existence. Eight years ago, she left her home in a destitute farming village and wound up here in Mongolpuri, a teeming warren of shabby apartment blocks and tarp-roofed shanties where grimy barefoot children, cargo bicycles, haggard dogs, goats, and cows jostle through narrow, trash-filled streets. Kiran earns about $1.50 a day sorting cast-off clothing for recycling. In short, she’s just another of India’s vast legions of anonymous poor.

Now, for the first time, her government is taking note of her. Kiran and her children are having their personal information recorded in an official database—not just any official database, but one of the biggest the world has ever seen. They are the latest among millions of enrollees in India’s Unique Identification project, also known as Aadhaar, which means “the foundation” in several Indian languages. Its goal is to issue identification numbers linked to the fingerprints and iris scans of every single person in India.

That’s more than 1.2 billion people—everyone from Himalayan mountain villagers to Bangalorean call-center workers, from Rajasthani desert nomads to Mumbai street beggars—speaking more than 300 languages and dialects. The biometrics and the Aadhaar identification number will serve as a verifiable, portable, all but unfakable national ID. It is by far the biggest and most technologically complicated biometrics program ever attempted.

Aadhaar faces titanic physical and technical challenges: reaching millions of illiterate Indians who have never seen a computer, persuading them to have their irises scanned, ensuring that their information is accurate, and safeguarding the resulting ocean of data. This is India, after all—a country notorious for corruption and for failing to complete major public projects. And the whole idea horrifies civil libertarians. But if Aadhaar’s organizers pull it off, the initiative could boost the fortunes of India’s poorest citizens and turbocharge the already booming national economy.

Photo: Jonathan Torgovnik

The Indian government has tried to implement national identity schemes before but has never managed to reach much more than a fraction of the population. So when parliament set up the Unique Identification Authority of India in 2009 to try again with a biometrically based system, it borrowed a trick used by corporations all over the world: Go to an outsourcer. The government tapped billionaire Nandan Nilekani, the “Bill Gates of Bangalore.”

Nilekani is about as close to a national hero as a former software engineer can get. He cofounded outsourcing colossus Infosys in 1981 and helped build it from a seven-man startup into a $6.4 billion behemoth that employs more than 130,000 people. After stepping down from the CEO job in 2007, Nilekani turned most of his energy to public service projects, working on government commissions to improve welfare services and e-governance. He’s a Davos-attending, TED-talk-giving, best-seller-authoring member of the global elite, pegged by Time magazine in 2009 as one of the world’s 100 most influential people. This is the guy who suggested to golf buddy Thomas Friedman that the world was getting flat. “Our government undertakes a lot of initiatives, but not all of them work,” says B. B. Nanawati, a career federal civil servant who heads the program’s technology-procurement department. “But this one is likely to work because of Chairman Nilekani’s involvement. We believe he can make this happen.”

The Unique Identification Authority’s headquarters occupies a couple of floors in a hulking tower complex of red stone and mirrored glass on Connaught Place, the bustling center of Delhi. As chair of the project, Nilekani now holds a cabinet-level rank, but his shop looks more like a startup than a government ministry. When I show up in February, the walls of the reception area are still bare drywall, and the wiring and air-conditioning ducts have yet to be hidden behind ceiling tiles. Plastic-wrapped chairs are corralled in unassigned offices.

“I took this job because it’s a project with great potential to have an impact,” Nilekani says in his spacious office, decorated with only a collection of plaques and awards and an electric flytrap glowing purple in a corner. He’s a medium-size man of 56 with bushy salt-and-pepper hair and a matching mustache. His heavy eyebrows and lips and protuberant brown eyes give him a slightly baleful look, like the villain in a comic opera. “One basic problem is people not having an acknowledged existence by the state and so not being able to access things they’re entitled to. Making the poor, the marginalized, the homeless part of the system is a huge benefit.”

Aadhaar is a key piece of the Indian government’s campaign for “financial inclusion.” Today, there are as many as 400 million Indians who, like Kiran, have no official ID of any kind. And if you can’t prove who you are, you can’t access government programs, can’t get a bank account, a loan, or insurance. You’re pretty much locked out of the formal economy.

Today, less than half of Indian households have a bank account. The rest are “unbanked,” stuck stashing whatever savings they have under the mattress. That means the money isn’t gaining interest, either for its owner or for a bank, which could be loaning it out. India’s impoverished don’t have much to save—but there are hundreds of millions of them. If they each put just $10 into a bank account, that would add billions in new capital to the financial system.

To help make that happen, Nilekani has recruited ethnic Indian tech stars from around the world, including the cofounder of Snapfish and top engineers from Google and Intel. With that private-sector expertise on board, the agency has far outpaced the Indian government’s usual leisurely rate of action. Aadhaar launched last September, just 14 months after Nilekani took the job, and officials armed with iris and fingerprint scanners, digital cameras, and laptops began registering the first few villagers and Delhi slum dwellers. More than 16 million people have since been enrolled, and the pace is accelerating. By the end of 2011, the agency expects to be signing up 1 million Indians a day, and by 2014, it should have 600 million people in its database.

Photos: Jonathan Torgovnik

Most Indians still live in rural hamlets like this, so getting them enrolled in Aadhaar requires some creativity. One evening not long ago, a man walked through Gagenahalli’s red-dirt streets beating a drum and calling the villagers to gather outside—the traditional way to make public announcements. He explained that the government wanted everyone to visit the village schoolhouse in the weeks ahead to be photographed.

A few days later, Shivanna, a stringy 55-year-old farmer—again, with just the one name—presents himself in a cement classroom commandeered by the agency. He doesn’t know what it’s all about, nor is he particularly interested. “When the government asks to take your picture, you just go and do it,” he shrugs. Shivanna takes a worn plastic chair at one of the four enrollment stations set up about the room. All the computer gear and the single bare lightbulb are plugged into a stack of car batteries and kerosene-powered generators—the village gets only a few hours of electricity a day from the national grid.

A young man in a polo shirt records Shivanna’s personal information in a form on his laptop. It’s bare-bones stuff: name, address, age, gender (including the option of transgender). He has Shivanna look into a camera mounted on the laptop. Once the Aadhaar software tells him he’s got Shivanna’s full face in the frame and enough light, he snaps the picture. The program runs similar quality checks on the agent’s work as Shivanna looks into the iris scanner and then puts his fingers on the glowing green glass of the fingerprint scanner. “We had to dumb it down so that anyone could learn to use the software,” says Srikanth Nadhamuni, Aadhaar’s head of technology, as he watches the scan progress.

About 100 miles east of Gagenahalli is Bangalore, the center of India’s booming IT industry. In one of its southern suburbs, across a busy street from Cisco’s in-country headquarters, sits the office building housing Aadhaar’s Central ID Repository. The information collected from Shivanna the farmer, Kiran the rag sorter, and every other person enrolled in the Aadhaar system gets sent here, electronically or via couriered hard drive.

This is Nadhamuni’s domain. He’s a trim, energetic, half-bald engineer with geek-chic rectangular glasses. His English is full of the awesomes and likes that he picked up in Silicon Valley, where he worked for 14 years. In 2002, he, his engineer wife, and their two kids returned to India, and a year later he and Nilekani launched a nonprofit dedicated to digitizing government functions. Nilekani even kicked the organization a few million dollars.

Some of the projects that Nadhamuni worked on—computerizing birth and death records, improving the tracking of schoolkids in migrant worker families—impressed upon him how much India needed a central identity system. When Nilekani asked him to be point man for the task of wrangling Aadhaar’s data, Nadhamuni says, “I was, like, delighted.”

The offices, like the identity program’s Delhi headquarters, are still under construction. When I tour them, rolls of carpet tied with string are stacked along a wall, and workers’ bare feet have left plaster-dust prints in a corridor leading to an unfinished meeting room. The rows of cubicles that will eventually accommodate roughly 400 workers are only about half full. The wall intended for a dozen video monitors showing incoming data packets is, for now, empty.

Photo: Jonathan Torgovnik

Each individual record is between 4 and 8 megabytes; add in a pile of quality-control information and the database will ultimately hold in the neighborhood of 20 petabytes—that is, 2 x 1016 bytes. That will make it 128 times the size of the biggest biometrics database in the world today: the Department of Homeland Security’s set of fingerprints and photos of 129 million people.

The unprecedented scale of Aadhaar’s data will make managing it extraordinarily difficult. One of Nadhamuni’s most important tasks is de-duplication, ensuring that each record in the database is matched to one and only one person. That’s crucial to keep scammers from enrolling multiple times under different names to double-dip on their benefits. To guard against that, the agency needs to check all 10 fingers and both irises of each person against those of everyone else. In a few years, when the database contains 600 million people and is taking in 1 million more per day, Nadhamuni says, they’ll need to run about 14 billion matches per second. “That’s enormous,” he says.

Coping with that load takes more than just adding extra servers. Even Nadhamuni isn’t sure how big the ultimate server farm will be. He isn’t even totally sure how to work it yet. “Technology doesn’t scale that elegantly,” he says. “The problems you have at 100 million are different from problems you have at 500 million.” And Aadhaar won’t know what those problems are until they show up. As the system grows, different components slow down in different ways. There might be programming flaws that delay each request by an amount too tiny to notice when you’re running a small number of queries—but when you get into the millions, those tiny delays add up to a major issue. When the system was first activated, Nadhamuni says, he and his team were querying their database, created with the ubiquitous software MySQL, about 5,000 times a day and getting answers back in a fraction of a second. But when they leaped up to 20,000 queries, the lag time rose dramatically. The engineers eventually figured out that they needed to run more copies of MySQL in parallel; software, not hardware, was the bottleneck. “It’s like you’ve got a car with a Hyundai engine, and up to 30 miles per hour it does fine,” Nadhamuni says. “But when you go faster, the nuts and bolts fall off and you go, whoa, I need a Ferrari engine. But for us, it’s not like there are a dozen engines and we can just pick the fastest one. We are building these engines as we go along.”

Using both fingerprints and irises, of course, makes the task tremendously more complex. But irises are useful to identify the millions of adult Indians whose finger pads have been worn smooth by years of manual labor, and for children under 16, whose fingerprints are still developing. Identifying someone by their fingerprints works only about 95 percent of the time, says R. S. Sharma, the agency’s director general. Using prints plus irises boosts the rate to 99 percent.

That 1 percent error rate sounds pretty good until you consider that in India it means 12 million people could end up with faulty records. And given the fallibility of little-educated technicians in a poor country, the number could be even higher. A small MIT study of data entry on electronic forms by Indian health care workers found an error rate of 4.2 percent. In fact, at one point during my visit to Gagenahalli, Nadhamuni shows me the receipt given to a woman after her enrollment; I point out that it lists her as a man. A tad flustered, Nadhamuni assures me that there are procedures for people to get their records corrected. “Perfect solutions don’t exist,” Nilekani says, “but this is a substantial improvement over the way things are now.”

For the past year or so, Mohammed Alam, 24, has spent his nights in a charity-run Delhi “night shelter” for the homeless. Inside the weathered cement building, nearly 100 men and one 3-year-old boy in various states of dishevelment sprawl on worn cotton mats in a gloomy open room. A bloody Bollywood action movie flickers on a small TV sitting on a folding table in a corner. The stench of ammonia wafts from the group bathroom across the foyer.

Alam looks markedly healthier than most of his compeers, his glossy black hair elaborately gelled and his teal shirt and jeans spotless. He left his home in Lucknow because of family problems he’d rather not specify and has been getting by in the capital ever since, doing odd labor jobs. In a good month, he pulls in about $50. That makes it hard to afford his own place to live. But the Unique Identification Authority came to enroll the shelter’s inhabitants a few weeks ago, and Alam just received a letter from the authority with his randomly generated 12-digit Aadhaar number.

The authority doesn’t issue cards or formal identity documents. Once enrolled, each person’s eyeballs and fingertips are all they need to prove who they are—in theory, anyway. For now Alam keeps the folded-up letter in his pocket. It serves as ID when the police stop him, he says. But more important, he just used it to open a bank account. “I tend to spend more money when it’s on me,” he says.

Banks, however, are in short supply in the countryside, where most Indians live; the one nearest to Gagenahalli is 7 miles away. That’s one reason only 47 percent of Indian households have bank accounts (compared with 92 percent in the US). So Indian financial institutions have begun introducing “business correspondents” into bankless areas, essentially deputizing some shopkeeper or other trusted local who has access to a little cash to handle villagers’ tiny deposits and withdrawals. Here’s how it’s supposed to work: Say Shivanna wants 50 rupees from his savings account. Instead of schlepping miles to an actual bank, he goes to the little kiosk down the road from his house. The guy in the kiosk scans Shivanna’s fingerprints with an inexpensive handheld machine. (There are several on the market already; other similar gadgets—and even cell phone apps—that scan irises are in the works.) Then he transmits the image via cellular network to the tech hub in Bangalore and gets a simple confirmation-of-identity message. (The same process works for deposits.) Once Shivanna’s identity is validated, the kiosk guy gives him his cash or deposit receipt, minus a small commission. Shivanna’s bank reimburses the kiosk guy. Shivanna saves time and money, the kiosk guy makes a little profit, the bank gets more capital, and the rising tide lifts all boats.

Photo: Jonathan Torgovnik

In practice, of course, all kinds of things might go wrong. “Some iris scanners can be fooled by a high-quality photo pasted onto a contact lens,” says a senior exec from a biometrics-equipment maker working on the project. Fingerprints can be lifted from almost anything you touch, and a laser-printer reproduction of one will have tiny ridges of ink that may fool scanners. Or a corrupt Aadhaar worker could pair a scammer’s name with someone else’s biometrics. The system is being built with open architecture so other agencies and businesses can add their own applications. The idea is to make Aadhaar a platform for all kinds of purposes beyond government benefits and banking, much like a smartphone is a platform for more than making phone calls. In January, the Indian Department of Communications declared Aadhaar numbers to be adequate ID to get a mobile phone. It’s easy to imagine the numbers being used to authenticate airline passengers, track students, improve land ownership records, and make health records portable. But opening up the Aadhaar system so widely makes it vulnerable. Each record is encrypted on the enroller’s hard drive as soon as it’s completed, and the central database will have state-of-the-art safeguards. Still, Sharma acknowledges, “there’s no lock in the world that can’t be broken.”

Anyway, Nadhamuni points out, credit card numbers are stolen all the time, but everyone still uses them because the card companies have come up with enough ways to spot when they’re being used fraudulently. In the big scheme of things, credit card fraud is a relatively small problem compared with the gigantic benefit of being able, say, to buy stuff online. He believes the same calculus will hold for Aadhaar. And if Aadhaar data is stolen, they have countermeasures to deal with it.

There’s also the question of whether India’s cell phone network, which will carry the bulk of the verification requests, can handle such a load. “We expect to be getting 100 million requests per day in a few years,” Nadhamuni says. “And the authentication needs to happen fast. The answer needs to come back in maybe five seconds.” Partly to meet that demand, the federal government is investing billions to massively expand the nation’s broadband capacity. “It’s not there yet,” Nilekani says. “But if someone had told you 10 years ago that there would be 700 million mobile phones in this country today, you’d say he was smoking something.”

The technological problems may pale compared to the potential civil liberties issues. Anti-Aadhaar protesters showed up at Nilekani’s January speech at the National Institute of Advanced Studies. Several anti-Aadhaar websites have sprung up. And members of parliament and prominent intellectuals have criticized the whole idea. (A Christian sect even denounced it as a cover for introducing the number of the Beast.)

Technically, Aadhaar is voluntary. No one is obligated to get scanned into the system. But that’s like saying no American is obligated to get a Social Security number. In practice, once the Aadhaar system really takes hold, it will be extremely difficult for anyone to function without being part of it. “I find it obnoxious and frightening,” says Aruna Roy, one of India’s most respected advocates for the poor (and, like Nilekani, one of Time’s 100 most influential people). India, she points out, is a country where people have many times been targeted for discrimination and violence because of their religion or caste.

Earlier this year, privacy concerns scuttled an effort to give every citizen of the United Kingdom a biometric ID card, and similar worries have slowed ID plans in Canada and Australia. “But the intentions were very different. It comes more from a security and surveillance perspective,” Nilekani says. “Many of these countries already have ID. In our situation, our whole focus is on delivering benefits to people. It’s all about making your life easier.”

The Unique Identification Authority is very deliberately not collecting information on anyone’s race or caste. But local governments and other agencies subcontracted to collect data are permitted to ask questions about race or caste and link the information they harvest to the respondent’s Aadhaar number. In Gagenahalli, for instance, agents asked villagers several extra questions about their economic conditions that the Karnataka state government requested. “I haven’t seen any agencies asking for caste or religion, but the fact that they can seems problematic,” admits a midlevel Aadhaar official who asked to remain anonymous. And while the agency has pledged not to share its data with security services or other government agencies, “if they want to, they can,” says Delhi human rights lawyer Usha Ramanathan. “All that information is in the hands of the state.” It’s not an unreasonable concern; in the wake of the Mumbai terror attacks, security is a major preoccupation in India. Armed guards, x-ray machines, and metal detectors are standard features at the entrances of big hotels, shopping centers, and even Delhi subway stations. Police officials have told Indian newspapers that they would love to use Aadhaar numbers to help catch criminals. And, in fact, some of the agency’s own publicly available planning documents mention the system’s potential usefulness for security functions. “We would share data for national security purposes,” Nilekani admits. “But there will be processes for that so you have checks and balances.” Every official I speak with, from Nilekani on down, seems impatient when I bring up this issue. They breezily remind me that there’s an electronic data privacy bill before parliament—as though the mere fact that the government is thinking about the issue is enough.

For supporters, the bottom line is simple: The upsides beat the downsides. “Any new technology has potential risks,” Nilekani says. “Your mobile phone can be tapped and tracked. One could argue we already have a surveillance state because of that. But does that mean we should stop making mobile phones? When you have hundreds of millions of people who are not getting access to basic services, isn’t that more important than some imagined risk?”

Indeed, Kiran, the mother of three at the Mongolpuri enrollment station, actively wants the government to have a record of her and her children. She’s a bit mystified when I ask if the idea worries her. If you’ve never read a newspaper, let alone fretted over your Facebook privacy settings, the question of whether the government might abuse your digital data must seem pretty abstract—especially when you compare it with the benefits the government is offering.

The first thing Kiran plans to use her Aadhaar number for, she says, is to obtain a city government card that will entitle her to subsidized groceries. “I’ve tried very hard to get one before, but they wouldn’t give it to me because I couldn’t prove I live in Delhi,” she says. Having that proof will take some other stress off her mind, too. She’s constantly afraid the police will order non-Delhi residents to leave the overcrowded slum, but now she has something to show them if they do.

Her three children come running up, fresh from having their own irises scanned. They’re excitedly waving their receipts for the numbers that will be attached to them for the rest of their lives. “It was fun!” 7-year-old Sadar says. “It wasn’t scary at all.”

Vince Beiser (@vincelb

Saturday, October 29, 2011

1748 - State depts refuse to accept UID cards as proof - TOI

A senior UID bureaucrat said that the card has no legal validity since the Congress-Nationalist Congress Party government had not issued a notification. "As per norms prescribed by the Centre, the state government has to notify the legal validity of the Aadhar card, and then only will it be accepted as an identity card and proof of residence. It appears that so far the state government has not issued the notification. There appears to be lack of coordination at all levels,'' he said.

The UID project was launched in the tribal Nandurbar district of north Maharashtra on September 30 last year in the presence of Congress president Sonia Gandhi and prime minister Manmohan Singh. When Nilekani proposed the card, the main purpose was to obviate the need to produce multiple documents to prove one's identity. As per official records, while three crore persons have registered for the UID project, 1.25 crore cards have been issued across the state.

The card is issued after personal verification of all documents, particularly proof of residence and date of birth, and is a valid document for identity to open a bank account, secure a driving licence or purchase a motor vehicle. "It was mainly for all who don't have an identity card," he said.

Besides most state departments, even regional transport offices were not accepting the card as proof of residence in Mumbai. A week back, when a Borivli resident approached the Andheri transport office, he was told that it was not valid as proof of residence and that he should produce a ration card issued by the food and civil supplies department or passport.

"They told me that not only the Aadhar card, but even the driving licence is not acceptable as proof of residence. Now, I am securing a ration card to establish my proof of residence. I was shocked to know the transport department is not accepting the Aadhar card as proof of residence," he said.

While there was no response from chief secretary Ratnakar Gaikwad on the card's legal validity, transport commissioner V N More said he will conduct an inquiry as to why it was not accepted by the Andheri transport office. "If the officers are at fault, we will take action against the erring staff," More said.

He said following specific instructions from the ministry of surface transport and highways, RTOs across the state have been told to accept the card as proof of residence while issuing driving licences and for registration of vehicles.

A top bureaucrat admitted that it in the absence of a notification, even if the cards are issued, most departments were reluctant to accept them as a legal document. "Apparently, the government plans to issue the notification after all Aadhar cards are issued across the state. We feel that it will be too late, as it will take at least two years to complete the exercise. Chief minister Prithviraj Chavan must step in ask all departments to accept the card as proof of residence," he said.

1747 - Probe ordered into Kerala govt move on online tracking of students -Write2Kill

In a letter to the Secretary of the Education Department, Govternment of Kerala, the NCPCR on Friday asked the department to investigate the matter and take further necessary action. A factual report, along with authenticated copies of the relevant documents, would have to be sent to the Commission within 15 days.

The report would have to look into the matter on priority basis and provide details on how the department planned to safeguard the children's right to privacy and dignity in the use of UID/ Sampoorna software.

The NCPCR has been constituted under the provisions of the Commissions for Protection of Child Rights (CPCR) Act, 2005 for protection of child rights and other related matters. One of the functions assigned to the Commission under Section 13 (1)(j) of CPCR Act is to inquire into complaints and suo motu cognisance in relation to deprivation and violation of child rights.

The Commision's move came by civil society activists Kamayani Bali Mahabal, Anivar Aravind and Usha Ramanathan drawing attention to a circular, based on which details of as many as 6 million students spanning over 15,000 schools in the state would be captured under the scheme. All schoolchildren would have had to have unique identification numbers (UID), which would help in tracking their movements in educational institutions and academic records. The circular said, “The headmasters of the schools should ensure that all students have filled in the forms before 31/08/2011, ordered by class and division. The education officers are directed to monitor these explicitly.”

The complainants said that a law to govern the UID project was yet to be passed by Parliament. The National Identification Authority of India Bill 2010 was introduced in Parliament on December 3, 2010, and sent to the Standing Committee of Finance on 20th December 2010. The committee has reportedly expressed serious reservations about the project. The project is, in other words, currently operating outside the protection of law.

“It has been acknowledged that there are abiding concerns about privacy that the project has to address before it can be allowed to proceed. There is a draft Privacy Bill that has not yet been introduced in Parliament. There are no protections that the law provides. There are no protocols about who can access the information, how the UID number may be used, what will happen if there is identity theft and identity loss. There are no protections against tracking and profiling. The collection of biometrics increases the concern,” they said.

“There is no means of controlling the recording and retrieval of data about children, and that is especially serious since our jurisprudence clearly states that the records relating to children except public exam marks should not be carried into adulthood. This is especially important where the child has had a difficult growing up and may have encountered problems of being a ‘neglected child’ or a ‘child in conflict with the law’. These are specifically proscribed from being carried into adulthood, with good reason. The UID, with its ability to link up data bases poses a threat to this important area of personal safety and protection of the child.”

Friday, October 28, 2011

1746 - UIDAI to launch online authentication project in Jharkhand next month - Economic Times

The identification system will be synced to the Mahatma Gandhi National Rural Employment Guarantee Scheme in five blocks of the state early next month, Nandan Nilekani, the chairman of the Unique ID Authority of India, said. The state government and banks will use this database to open bank accounts and transfer funds for thousands of beneficiaries under the Centre's flagship scheme.

The authority, tasked with issuing a unique 12-digit 'Aadhaar' number to all Indian residents, is banking on the success of the pilot project to build a case for more funds and wider scale of coverage. It is also hoping to counter recent criticism of its administrative structure and expenditure.

"We have just started a pilot project linked to NREGA in Jharkhand and by next month we will launch the first online authentication system, which can give banks access to the details of beneficiaries online," Nilekani said.

The 'Aadhaar' number will be the key to the holder's personal details and is meant to serve as a single source of authentication for a host of public services. Through this, the authority hopes to check embezzlement of public funds and weed out fake identities.

The result of the Jharkhand project will help authorities decide whether the system can be scaled up and used nationwide for opening bank accounts, issuing of driving licences, ration cards, passports, etc.

"This will also be used to enable payments through business correspondents in NREGA using a biometric authentication system," Nilekani added.

So far, the Reserve Bank of India and the finance ministry have mandated the UIDAI number as a valid "know-your-customer" document for opening bank accounts, but are yet to allow online verification.

The authority, which has enrolled around 110 million people in its systems, is talking to various stakeholders, such as telecom department, to make 'Aadhaar' a valid document to access services.

Nilekani said that three states have recognised the system's identity proof for various government services. "We are trying to make more state governments agree to this," he added.

The authority has come under fire from some government departments over its functioning and spending.

In September, the Registrar General of India (RGI), which is also collecting biometric data as part of its National Population Register, said the data collected by UIDAI's registrar agencies was not reliable, as they were not following the parameters set for the NPR.

The criticism led to UIDAI's demand for 15,000 crore to scale-up coverage being rejected by the Expenditure Finance Commission last month.

"The Registrar General has expressed some reservations on using the data collected by non NPR registrars. That is the only contention which will be resolved by the cabinet," Nilekani said.

The decision on whether UIDAI-appointed registrars can collect data will be taken by the Cabinet Committee on UIDAI.

The UIDAI was also criticised by some sections of the Planning Commission on its administrative structure while the country's official auditor, CAG, initiated a pilot performance audit on the authority on October 3.

"We have resolved all issues and are doing our job. The CAG is doing its job. We have nothing to hide. It's all transparent," Nilekani said.

1745 - No good deed goes unpunished - Mid Day

The centre has been closed suddenly and shifted to Prasad Nagar in central Delhi. The centre was in operation from July 3 to October 13, a day after MiD DAY carried the news report.

Apart from shifting the centre, the UID in-charge is demanding rent and electricity charges from Dr Sanjay Dhingra, who has provided his clinic for the facility free of cost. "The UID centre in-charge is pressurising me to pay rent and electricity charges. He is saying a machine has broken down at his centre and he will use the money to pay for the losses," Dr Dhingra told MiD DAY. It may be recalled that Dr Dhingra was also deputed as introducer in the area and he had introduced 952 residents.

"When all local schools had rejected the proposal to provide space to start a UID centre, Dr Dhingra offered his place voluntarily. Now when hundreds of residents have registered at this centre and hundreds more are still to register, it is unfortunate to close it," said Jameel, a resident of Gali Tajran, Suiwalan. Another resident, MN Khan, demanded a new UID centre to cover those who don't have UID cards.

According to sources, the centre has now been shifted to Arya Samaj Mandir, Prasad Nagar.