8th November 2010

With the recent controversy over Octopus Rewards Ltd, and the way it had been using the data supplied by its customers, we thought this would be an ideal time to highlight a common misconception regarding the Hong Kong Identity Card (HKIC) number, or HKID.

Identifier, not authenticator

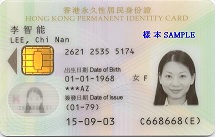

A unique, unused HKID is assigned to each resident of Hong Kong aged 11 years or older under the Registration of Persons Ordinance and the Registration of Persons Regulations, and this is displayed on the face of his HKIC, along with his date of birth and various other data. The Smart ID Card also contains a chip with a small processor and some encrypted data, including the photo image, and "templates" of the left and right thumbprints. The templates are measurements of thumbprints, not images of the prints - you could not reproduce a thumb print from the measurements.

The HKID is what its name suggests - an identifier. It is unique to the holder. It is not an authenticator, like a password or PIN. Indeed, PIN, which stands for "personal identification number" is a misnomer - it doesn't identify you at all. It authenticates you when you use an automated teller machine or a web site that requires such a number. Numerous people may have chosen to use the same secret number - so it can't be an identifier. A PIN should be called a PAN - personal authentication number.

The HKID, in itself, should not be regarded as "personal data" or a secret. It is nothing more than an identifier. It doesn't say anything about you. The number does not include your age, gender, blood type, income or anything else. It is not much different to your name, which is almost an identifier; we could say, a "near-identifier", because you probably have a different name to more than 99% of the population, and your name may even be unique.

Your HKID is recorded in many aspects of life in HK, for example:

If you visit a secure office building, particularly after hours, then you may be asked for identification at the front desk, and your HKIC number will be recorded. A pass may then be issued to you. It's entirely reasonable - you wouldn't let complete strangers into your home, would you?

If you open a bank account, the bank will record your HKID (or passport number), so that it knows which unique person it is dealing with. It may ask to see your card again when you withdraw large amounts of money, as well as asking for your manual signature of course. This reduces fraudulent withdrawals, which reduces banking costs.

If you are appointed by the court as a liquidator of a company, then you need to be identified by your HKID in gazette notices such as this one, so that people know exactly whom they should make claims to. So the HKID of anyone who has ever been appointed a liquidator is already in the public domain - it is not a secret.

HKIDs are often included in legal contracts for sale and purchase of property, publicly filed with the Land Registry. That's because the owner needs to be able to prove that a property is owned by him rather than by someone else with the same name, and the buyer wants to know that he is dealing with the real owner.

The HKID (or a passport number) of anyone who has been a director or secretary of a company registered in HK is recorded on filings made with the Companies Registry, so that shareholders, creditors or anyone dealing with the company knows the identity of anyone who is or was running it. These forms are open to inspection or copying. As a company director, your editor David Webb's HKID is there, and to save you the cost of looking it up, here it is: P135143(9). There you go. No big deal. Not a secret. Just an identifier. Now if you ever meet someone claiming to be that David Webb, you can ask to see his ID card.

Incidentally, the last character in brackets ( ) is actually not part of the HKID. It is a check digit which depends on the characters in the HKID, resulting between 0-9 or A. It is generated by a fairly simple formula, and is used to check for errors, because if you get one character wrong in the ID, then the check digit will be wrong. You can use our new online HKID check digit generator to calculate the check digit of any HKID - try it and see! Hours of fun for all the family.

Government encouraging the abuse of HKIDs

In recent (30-Aug-2010) consultation conclusions on some company law reforms, the Financial Services and Treasury Bureau of the Government said (page 9) that it will delete the last 3 digits of any ID number in future filings before displaying them. This is a naive and misguided move. As the Law Society put it in their submission (page 4):

"Identification numbers should be recorded and disclosed in full as it is a unique piece of information for identifying a person; the name of a person is not. Persons with identical names are not uncommon. An identification number is not a reliable tool for authenticating the identity of a person in electronic or telephone transactions. Use of identification number for authentication purpose is itself a misuse and should be discouraged."

The Government, in its conclusions, said "the remaining digits (together with the name) should be sufficient to identify the individual persons". That directly contradicts its own consultation paper, which said (p54) "The option of masking 3 or 4 digits of an identification number would not serve the purpose of identifying a person as there are cases of persons with the same name having similar identity card numbers".

The Government proposes to allow any company director to pay a fee to get their HKID in old filings partially blacked out - but that doesn't stop people accessing the information before the law changes and keeping it. Put simply, you cannot "unpublish" something once it is out there.

By treating HKIDs as secrets, the Government is encouraging the use of the HKID as an authenticator. Instead, the Government should be publishing full HKIDs in its various public notices (just as it does for liquidators), and should embark on one of its publicity campaigns to remind people that HKIDs are not secrets and should not be used as passwords.

The easiest way to stop the abuse would be to give clear notice that in say, two years' time, the full register of all HKIDs and the corresponding names will be published, so that nobody will rely on them as authenticators after that. Two years ought to be enough time for all commercial users to modify their systems to use more reliable authentication.

The SSN problem in the USA

By encouraging the use of HKIDs as authenticators, the HK Government is on the road to increasing abuse and higher levels of fraud in the economy. The USA provides a case study in this: since 1936, the Social Security Number (SSN), originally designed just to track social security contributions, has become widely used as an identifier for many purposes.

The US Government has gone the wrong way about dealing with the problem - actually discouraging disclosure of SSNs, thereby encouraging firms to rely on them more as authenticators, even though any halfway-competent identity thief knows how to find them. You cannot put the genie back in the bottle. Instead, the US Government should adopt a national identity card system with biometric authentication and digital certificates, of the type used in an increasing number of countries. With such a system, the economic losses of identity theft could be dramatically reduced. Instead of just claiming an identity with an SSN number, citizens would be able to prove their identity.

Abuse of the HKIC number as an authenticator

The companies in HK which are abusing the HKID as an authenticator are mostly low-ticket service providers such as phone operators, pay TV operators and utility companies. They typically ask for your HKID when you call them by phone. That's because they don't want to make the necessary investment to set up a password or PIN and mail it to you.

It's their choice, but they should not claim reliance on the HKID later on if it turns out that they had been speaking to an impostor. If they don't have secure authentication, then the customer can't be held liable for changes to an account made by an impostor, and the operator can be held liable for any damage to the account holder. Taking on that risk is a commercial judgement for the operator, weighed against the cost of fraud. Ultimately, if a service provider is relying on non-secret information to authenticate someone, such as a phone number, address or date of birth then they are never going to be 100% certain who they are dealing with.

HKIDs in IPO refunds

In another botched bit of policy-making, on 22-Jul-2004, in order to deal with the problem of theft of IPO refund cheques from the mail, the SFC announced that banks would print the applicant's HKID or passport numbers on the cheques. This was a good move, because it meant that the cheque could only be paid into the account of someone who not only used the same name but also had the correct ID number associated with his bank account, but the mistake was this: with false concerns about data privacy, they decided to mask out the 5th and 6th characters of ID numbers, for example, "A123**6". They treated the ID number as a secret rather than an identifier. The unintended consequence was that this facilitated multiple applications by people who varied the masked digits in their ID number. Theoretically, you could make 100 applications that way, or 10 if the registrar was verifying the check digit.

So on 23-Mar-2007, the SFC announced a changed system in which the two masked digits would be randomly selected from IPO to IPO. Of course, there would be no incentive for multiple applications if the allotments were just a flat percentage of the application size, but they aren't, and that's a story for another day.

Who is who?

As readers will know, we run a "Webb-site Who's Who" of important people in Hong Kong, accessible from the search box at the top of every page, and assembled entirely from public information. We absorb the cost and make it freely available in the public interest. One of the ongoing challenges we have is avoiding mistaken identity when referring to real people. The Government's announcements of appointments to statutory or advisory bodies often don't even use the full name of the person they are appointing, making them even harder to identify. They might as well announce that they have appointed "Mr Anonymous". This hardly encourages confidence in the accountability of appointed persons for their work on these public bodies.

A recent example was the appointment of "Irene Chow" and "Dennis Chan" to the Polytechnic Council, as notified in the Gazette, and another is the appointment of "Alvin Yip" and "Joe Ngai" to museum advisory panels. These names have many holders in HK, and the announcement contained no other clues as to who these people were. In each case, we had to contact the Government and ask for the full names. It would be far more sensible for the Government to announce the full name and the identity number of appointees, so that we all know exactly who they mean. Again, it is only an identifier, not an authenticator.

Similarly, listed companies should use identity card numbers (or passport numbers, for overseas directors who do not have a national ID card in their home country) in appointment announcements and annual reports. These numbers are already filed when they notify the appointment to the Companies Registry, but not in the announcement filed with HKEx. Yes, we could get the information from the registry (until they delete it), but that involves using their ridiculous and unnecessary pay-per-view system. They actually make far more profit than the revenue they get from the pay-wall, so they should knock it down and allow free open access. Filing fees would still bring them a profit.

With the increasing prevalence of mainland individuals on the boards of listed companies, the mistaken identity problem is increasing. For example, we have 7 of "Li Jun" in our system. Fortunately, the Listing Rules require the age of directors to be disclosed, otherwise it would be even harder to distinguish them. If the Listing Rules required a national ID number to be published, this problem would vanish.

Smart ID's unused potential

One of the sad things about the Smart ID card is that, largely through lack of Government effort, its full potential has not yet been exploited. All of the "card-face data" - the text on the card that anyone can read with their eyes, is encrypted on the card's chip so that only authorised Government departments can access it using distributed keys. So far, only public libraries have the keys. But if anyone can read the data printed on the face of the card, then why not allow access to the electronic version of the same data when the card is presented to a reader?

Apart from card-face data, there are thumbprint templates in every card's chip, and these are used when you go through the fast channels at the mainland border or at the airport. But the thumbprint system is only used by the Government's immigration department, and has not been made available to any other service provider.

The way the thumbprint templates are compared at the airport and border controls is "off-card" - you put the card into a reader, take it out again, walk through the first gates, and then put your thumb on a reader. If it matches, the second gates let you through. If it doesn't match, then alarm bells ring, a big metal cage drops on you from the ceiling, you get tasered, and men in boots arrive and tell you to take off the silicone mask.

So after you remove your card from the reader, the immigration machine must temporarily have your thumbprint template, and the machine then decides whether your thumb matches the template. However, the card's CPU is capable of making the comparison itself, "on-card", so that the encrypted templates never leave the card. Installing this additional mode would allow the Smart ID system to be opened up to commercial users for authentication purposes, without exposing the thumbprint templates.

If the private sector could use the card for authentication, then there would be almost zero risk of forged or stolen cards being used to open bank accounts, obtain credit, or anything else. The thumbprint of the forger or thief using the card simply would not match the template on the card. Users could also use card-readers with a built-in thumbprint reader online (attached to their PC through a USB port), to authenticate themselves without having to remember all their different pin numbers and passwords. You could even open a bank account that way - online authentication using digital certificates would prove who you are. Using the HKIC and thumbprint would also save banks from issuing so many of those little one-time password generators to achieve 2-factor authentication.

The technology for thumbprint authentication is well established. The HK Smart ID Card runs the MULTOS operating system, and applications such as Match-on-Card from Precise Biometrics will run on it.

Still carrying a driving licence

When the Smart ID was designed, there was also a plan to drop the requirement that we carry driving licence cards when we drive, and instead, just present your HKIC and thumb if you are stopped by a police officer, to verify your identity. The licensing data is stored on back-end government computers, not on the card. So far though, the Government has yet to follow through, and we are still carrying around driving licenses. The physical licenses are only really necessary if you need to show proof of your driving licence to a car rental company.

E-purse

There was also a plan in 2002 for an "e-purse" on the card - a segregated area which would store electronic legal tender issued by the Hong Kong Monetary Authority. There is still space reserved on the card for that, but there is no timetable for implementing it.

The cash balance can be kept on the card rather than in a back-end database like the Octopus system. Given the recent controversy over the way Octopus has been behaving, and the fact that it charges merchants 1% on every transaction, there is certainly a case for the HKMA to revisit the proposal for electronic money. For one thing, it would reduce the cost and security issues associated with the "bearer bills" or bank notes currently in circulation, and complaints over what to do with small coins.

The Hong Kong Monetary Authority should publish proposals for activating the e-purse function on the cards. Nobody would have to use it if they did not want to.

Global PIN

There is also a "Global PIN utility" in every Smart ID card, which remains unused, but could be activated on a voluntary basis by the card holders. LegCo was briefed (p7-9) on this back in June 2002, and since then it has been quietly forgotten. The function could be activated using a thumbprint reader, then the user would choose a PIN, which would remain secured in the card. The PIN could then be used along with the thumbprint for 3-factor authentication: something you have (the card), something you know (the PIN), and something you are (the thumbprint).

The Smart ID Card has been issued since 23-Jun-2003. While there may have been governmental caution over fully utilising the potential at the outset, citizens have grown familiar with it over the last 7 years, and accept the convenient use of the thumbprint for authentication at immigration control points. They should be more than ready to accept wider usage. Meanwhile, the cost of card/fingerprint readers has dropped, so the widespread adoption of cheap USB readers for online authentication would be more feasible, if the Government would allow it. Given the high cost of running over-the-counter transactions with members of the public, it would likely save the Government money in the long-run to hand out a free card reader to each user and let them conduct their business online from their home or office.

Over 7 years after the Smart ID Card was launched, it is time for the Government to realise its full potential and economic benefits. In the meantime, the Government should stop treading HKIDs as secrets and publish the full HKID register of numbers and names, to remove the myth that the numbers are a reliable means of authentication.

© Webb-site.com, 2010