Sunday, Nov 14, 2010

Somehow, the PDS became a political priority in Chhattisgarh and a decision was made to turn it around, instead of siding with the corrupt dealers who were milking the system.

Other reports from Chhattisgarh suggest that this is not an isolated success. One survey of food-related schemes, conducted in September-November 2009 in eight Blocks spread over the state, found that 85 per cent of the cardholders were getting their full 35 kg of grain every month from the PDS (others were getting at least 25 kg). Only two per cent of the entries in the ration cards were found to be fake.

Eliminating middlemen

One of the early steps towards PDS reform was the “de-privatising” of ration shops. In Chhattisgarh, private dealers were allowed to get licences for PDS shops from 2001 onwards (before that, PDS shops were run by the state co-operatives network). This measure allowed the network of ration shops to widen, but also created a new nexus of corrupt players whereby dealers paid politicians to get licences as well as protection when they indulged in corrupt practices. In 2004, the government reversed this order (despite fierce opposition from the dealers) and put Gram Panchayats, Self-Help Groups, Van Suraksha Samitis and other community institutions in charge of the ration shops. Aside from bringing ration shops closer to people's homes, this helped to impart some accountability in the PDS. When people run their own ration shop, there is little incentive to cheat, since that would be like cheating themselves. Community institutions such as Gram Panchayats are not necessarily “people's institutions” but, nevertheless, they are easier for people to influence than corrupt middlemen or the government's bureaucratic juggernaut.

Another major reform was to ensure “doorstep delivery” of the PDS grain. This means that grain is delivered by state agencies to the ration shop each month, instead of dealers having to lift their quotas from the nearest godown. How does this help? It is well known that corrupt dealers have a tendency to give reduced quantities to their customers and sell the difference in the black market (or rather the open market). What is less well understood is that the diversion often happens before supplies reach the village. Dealers get away with this by putting their hands up helplessly and telling their customers that “ picche se kam aaya hai” (there was a shortfall at the godown). When the grain is delivered to the ration shop, in the village, it is much harder for the dealers to siphon it off without opposition. Truck movements from the godowns to the ration shops are carefully monitored and, if a transporter cheats, the dealers have an incentive to mobilise local support to complain, as we found had happened in one village.

These two measures (de-privatising ration shops and doorstep delivery) were accompanied by rigorous monitoring, often involving creative uses of technology. For instance, a system of “SMS alerts” was launched to inform interested citizens (more than 15,000 have already registered) of grain movements, and all records pertaining to supplies, sales, timelines, etc. were computerised. This involved much learning-by-doing. For instance, at one point the state government tried distributing pre-packed sacks of 35kg to prevent cheating, but the practice had to be discontinued as it was found that these sacks were being tampered with too. Therefore, in recent months, a move towards electronic weighing machines has been initiated.

Perhaps the most important step was improved grievance redressal, based, for instance, on active helplines. Apparently, the helplines are often used by cardholders, and if a complaint is lodged, there is a good chance of timely response. Further, action is not confined to enquiries — in many cases, FIRs have been lodged against corrupt middlemen and it is not uncommon for them to land in jail (there was at least one recent case in Lakhanpur itself). Grain has also been recovered from trucks that were caught off-loading their stocks at unintended destinations.

Increased transparency

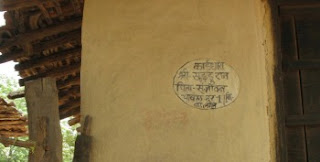

Greater transparency is an important step towards corruption-free administration. This is one important lesson from the National Rural Employment Guarantee Act (NREGA). “Information walls” in Rajasthan, whereby the names and employment details of all Job Card holders in a village are painted on the walls of the Gram Panchayat office, can help eliminate bogus Job Cards and fudged Muster Rolls. The NREGA's Monitoring and Information System (MIS), which computerises all records and makes them available on the Internet, is another important transparency measure that people are slowly learning to use.

Enhancing ‘Voice'

Turning to the “demand side” of the story, the most significant step in Chhattisgarh was a major expansion in the coverage of the PDS. In what is widely seen now as a shrewd political move, Raman Singh (BJP leader and current Chief Minister) revamped the PDS ahead of the 2007 state elections. Today, close to 80 per cent of the rural population — including all SC/ST households — is entitled to PDS grain at either one or two rupees per kilo. The fact that most rural households have a strong stake in the PDS has generated immense pressure on the system (ration shops in particular) to deliver.

Expanded PDS coverage and lower issue prices have both contributed to enhancing the voice of otherwise poor and disempowered rural cardholders. As Rajeev Jaiswal (Joint Director, Food and Civil Supplies) put it: “At the moment we are only using the voice of 80 per cent of the rural community. When the PDS is universalised, the entire community including the better educated and more vocal sections will start putting pressure on the system.”

Political move

Ultimately, however, it is political will that seems to matter most. Somehow, the PDS became a political priority in Chhattisgarh and a decision was made to turn it around, instead of siding with the corrupt dealers who were milking the system. When political bosses firmly direct the bureaucracy to fix a dysfunctional system, things begin to change.

The fact that government functionaries were under enormous pressure to make the PDS work was evident in Lakhanpur. For instance, monitoring grain movements had become one of the top priorities of the patwaris and tehsilars. The tehsildar mentioned that the PDS was the first agenda item whenever meetings were held at the district level. The political pressure was also manifest in their willingness to stand up to vested interests, e.g. by arresting corrupt middlemen and taking them to Court if need be.

It would be naïve to think that the revival of the PDS in Chhattisgarh reflects the kind-heartedness of the state government, especially in the light of its contempt for people's rights in other contexts. It was a political calculation, nothing more. But it worked, and it can happen elsewhere too.

Jean Dreze and Reetika Khera are associated with the G.B. Pant Social Science Institute, Allahabad University.